Knowledge Centre- Subject Index Main Help page |

Aerial Photography

by Tim Slater

Part 1 - The Pre-Cursor 1849 to August 1914

Part 2 - The Beginnings August 1914 to January

1916

Part 3 - Aerial Photography comes of age

Part 4 - The Uses for Aerial Photography

Part 4 - The Uses for Aerial Photography

Foundation Material

During the retreat from Mons in 1914 the scale of the movement involved meant that there was no requirement for detailed large scale maps to support the BEF. The first demand for large scale detailed mapping came after the battle of the Aisne as the front line began to stabilise. At this time with no trained surveyors available the BEF had to make do with the inaccurate 1:80,000 French mapping enlarged and redrawn at the Ordnance Survey Office Southampton. These enlargements were completely unsatisfactory, reproducing and magnifying the errors on the original that introduced gross positional errors. What was needed was a new field survey of the BEF operational area. In November 1914 two trained surveyors arrived in France as part of the First Ranging Section RE’s. These two surveyors were tasked with completing a survey that would enable a more accurate map to be produced in as short a time as possible. Their field work started on the 25 January 1915 and by the 28 February all the field sheets were passed to the Ordnance Survey for reproduction. The resulting 1:20,000 scale map was a vast improvement on the previous 1:80,000 enlargement (Winterbotham, Survey on the Western Front. pp. 6-7.). Its comparative accuracy improved the targeting accuracy of the British artillery and led to demands for accurate mapping of the German held territory.

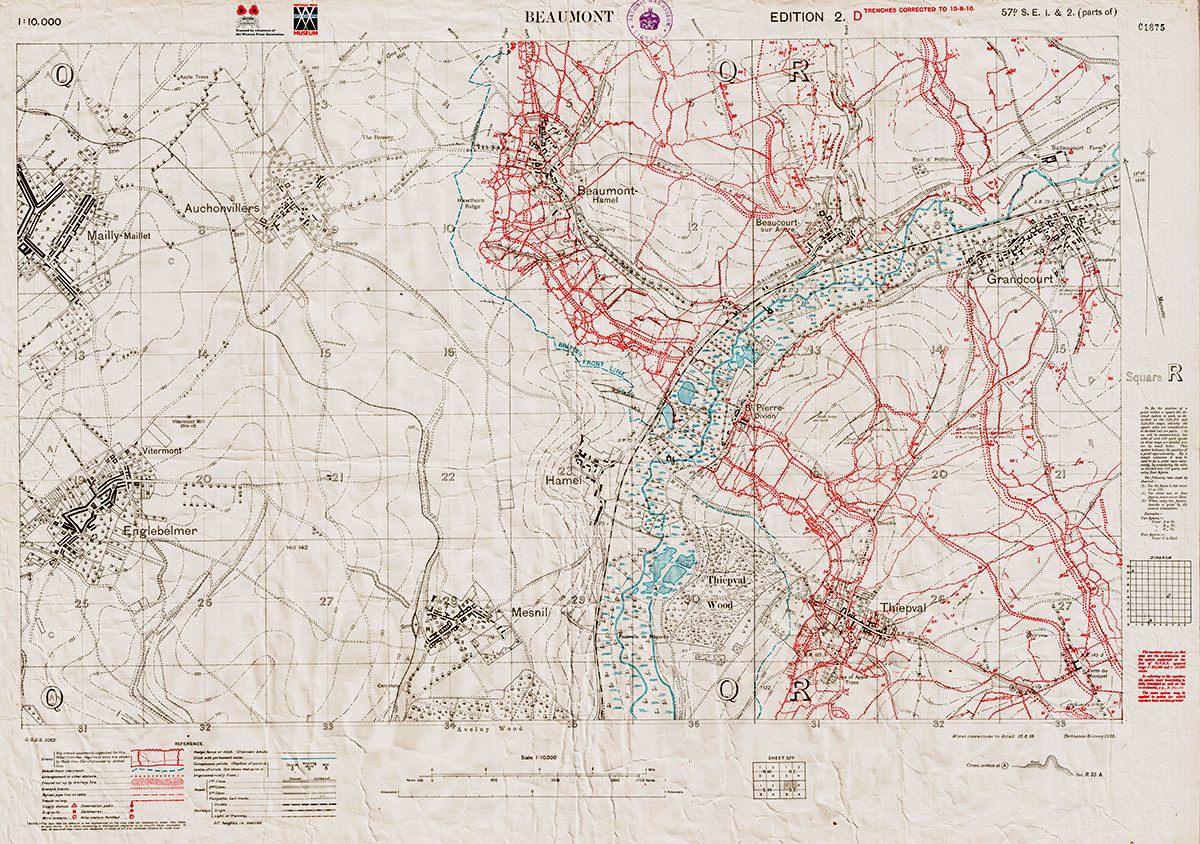

As mentioned previously, the responsibility for mapping the German-held territory rested with the GS Intelligence. However, the success of the Neuve Chapelle battle map ultimately led to the formation of Army Topographical Sections that became responsible for all map production in their Army’s area of interest. By the end of 1915 a newly created series of 1:10,000 base map sheets overprinted with the tactical detail of the German defensive positions had been produced. Aerial photography was the primary source used to derive both the topographical and intelligence detail displayed on the mapping.

Figure 14. 1:10,000 scale trench map dated 15.8.16 (source: WFA TrenchMapper).

Illustrated above (Figure 14) is a standard British 1:10,000 scale trench map overprinted in red with the German defensive positions. From 1916 maps of this type would be found adorning the walls in HQ’s and Intelligence sections throughout the BEF. The BEF now had a coherent framework on which to build a COP. The real challenge was to maintain the pictures currency to ensure a high level of situational awareness at all levels of the BEF.

Situation Awareness

During 1915, map production and map revision time, from the start of drawing to receipt of the map ready for use, took about two weeks. By 1916 the pressure of work at the Ordnance Survey had extended the production timescale out to four weeks (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 87.). As a consequence by the time a map was received at the front it was already out of date. This issue of currency was appreciated as early as the battle of Loos in 1915 when copies of aerial photographs were circulated so that staff and regimental officers could make hand written amendments to their maps (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 108.). During Loos, Romer (First Army Maps and Printing Section 1915) had his section working through the night producing and printing special map sheets showing the new detail derived from that day’s aerial photographs; these sheets were sent by dispatch rider to the affected units (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 110.).

Aerial Photography Limitations

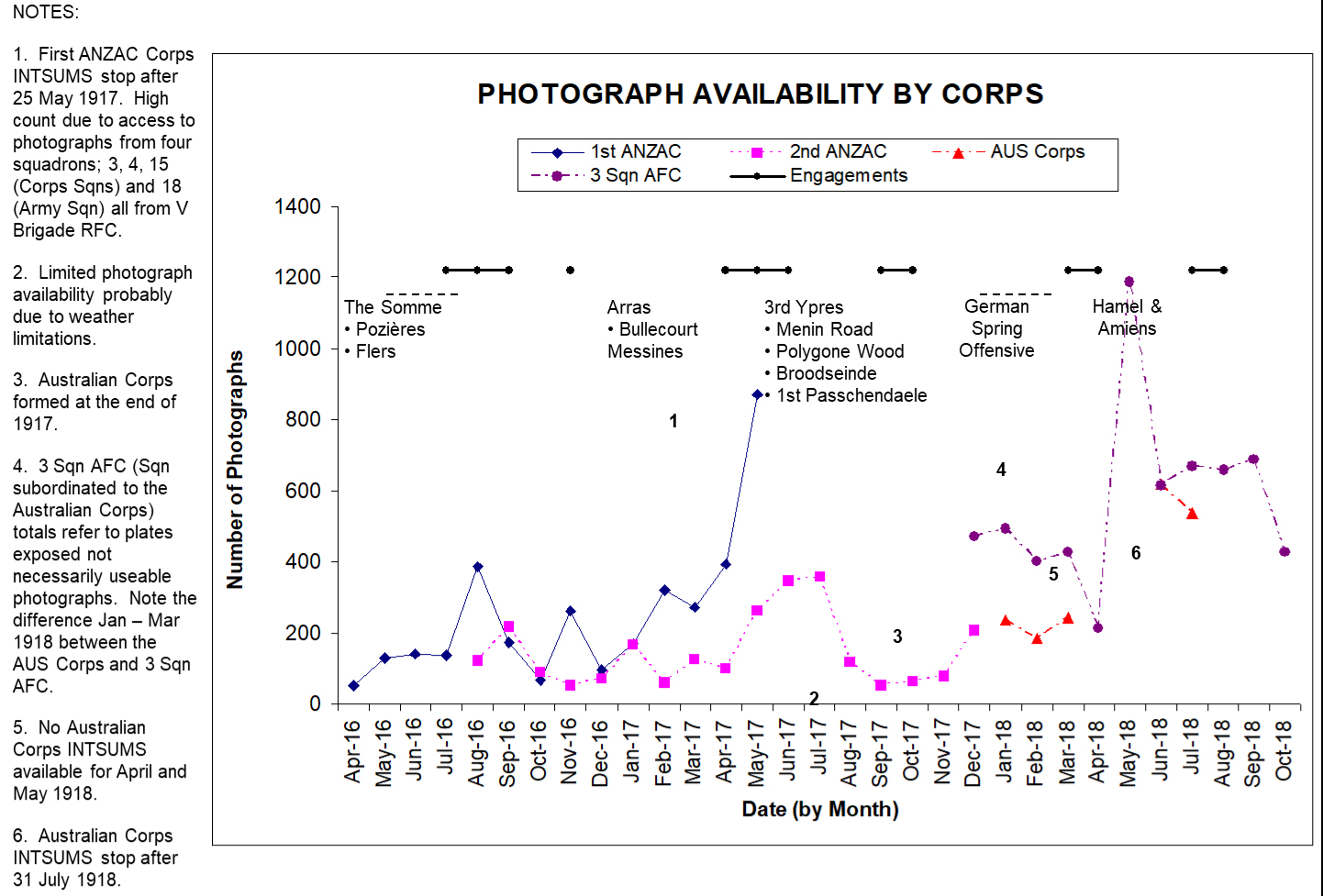

Aerial photography was proving central to maintaining situation awareness, although it was not a panacea but had marked limitations which included; a lack of persistence, weather dependency, and a slow (relatively) response time. Aerial photography lacked the persistence of visual reconnaissance; it was after all ‘a snap shot in time’. But to counter this it did provide a permanent record not prone to memory failings, in addition the ability to revisit an area of interest through a collection of photographs, the HOC, gathered over time proved invaluable for change detection. Weather played a key role in the successful collection of aerial photography. The poor weather at the end of Third Ypres is probably one of the reasons why II ANZAC Corps’ photograph availability was so low during the period (Figure 15). Response time proved problematic during the war. Much has been made of the ‘speed tests’ demonstrated during the Somme where from aircraft landing to processed prints arriving at Headquarters took as little as 30 minutes (Finnegan, Shooting the Front. p. 75.). It should be noted that photograph processing, printing and delivery was not the whole picture. Including tasking and flying time, plus time for interpretation and product dissemination; any response would have be extended to several hours or even longer as illustrated by the Lambert (Royal Scots Company Commander 1917) anecdote above (part 3). In the static warfare of the Western Front this was less of an issue, which was tempered further through regular pre-planned photograph collection. The intent, weather permitting was to photograph the German trench system up to a depth of 3,000 yards every five days, and the counter-battery area every 10 days (B.E. Sutton, ‘Some Aspects of the Work of the Royal Air Force with the B.E.F. in 1918’, RUSI Journal, 67 (1922:Feb./Nov). p. 339.). During operations this tempo would obviously change. At Messines in 1917, aerial photographs of the German defences were taken every day during the preliminary bombardment, and the known artillery positions every two days (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 304.). This meant that even outside of operations a regular supply of photographs was available and distributed.

Access to Aerial Photography

As has been outlined, access to aerial photography and intelligence derived from it expanded down through the echelons of the BEF throughout the war. Figure 15 illustrates the availability of aerial photography to the Australian forces in France from April 1916 to October 1918 based on a review of I and II ANZAC Corps and the Australian Corps daily INTSUMS over the period. Bearing in mind that the Dominion forces were fully integrated and supported within the BEF, it is probably fair to assume that the availability illustrated is representative for all the Corps in the BEF from 1916.

Figure 15. Aerial Photograph availability derived from I and II ANZAC Corps and the Australian Corps daily Intelligence Summaries.

The Distribution of Photographic Prints

The distribution of photographic prints came in three forms, raw, annotated or as part of a specialist product for example a mosaic or stereo pair of photographs. During 1915, with the RFC Wing photographic sections managing the distribution of prints, the majority went out raw with the recipients expected to carry out their own interpretation and build their own specialist products. In 1916, following the establishment of squadron photographic sections, an initial proof distribution to the demanding unit/s was handled by the squadron. A full distribution would be made by the RFC Wing following the transfer of the negatives. Again, the majority of the prints went out raw. With aerial photographs now being seen as a direct source of intelligence by the artillery and the infantry, the demand for prints and specialist products soured. While the print distribution process struggled to cope with the new demand the print production process failed; resulting in frequent delays in the delivery of prints to the subordinate units. The BEF’s response was twofold, to fill the gap with text reporting and find an organisation that could carry out the necessary bulk printing. The qualitative improvement in the text reporting noted previously in the First ANZAC Corps INTSUMS during 1916 illustrates the success of the text reporting approach. The text reporting was structured around the map grid referencing system to facilitate hand written updating of the available mapping:

‘(A). A well defined track evidently considerably used, leading from the communication trench at R.35.a.6.2 ½ . and proceeding in a N.E. direction to R.35.b.4 ¼ .8. where it meets the new trench dug to protect COURCELETTE from the South.’. (Australian War Memorial, FIRST ANZAC CORPS INTELLIGENCE SUMMARY to 6 p.m. on 31st July to 6 p.m. on 1st August ‘17, AWM4/1/30/7 Part 1.)

Text reporting also had an unforeseen corollary; not only did it widen the availability of photograph derived intelligence but it also increased the demand for it. From October 1916 the Army Printing and Stationary Service (AP&SS) had set up a section in Amiens that could produce 5,000 prints a day. Initially only print production runs greater the 100 were authorised. By the end of the Somme each army had its own AP&SS section bulk reproducing prints and specialist products (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 227.). With the printing problem solved by the end of 1916, a corresponding reduction in the text report could have been expected. This was not the case, text reporting via the updated map was able to reach a wider audience than the distributed print.

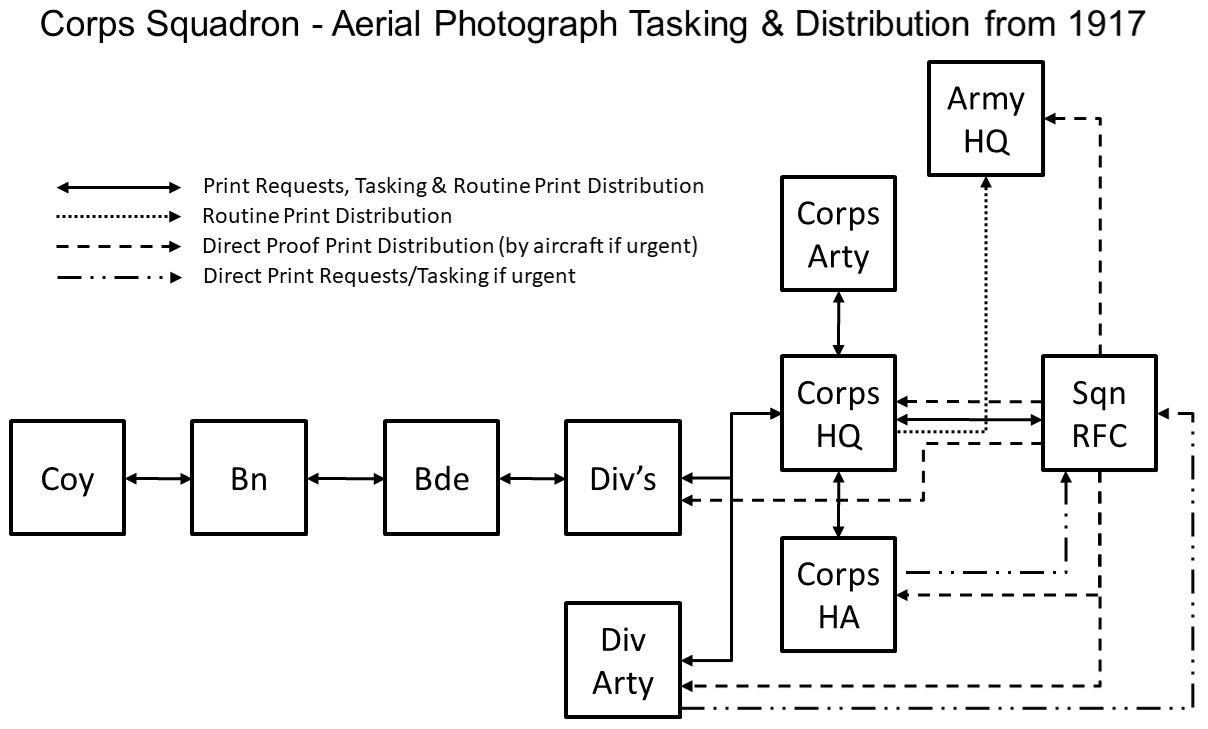

The establishment of the BIS’s in 1917 changed the print distribution dynamics and made the RFC squadron the coordinating unit (Figure 16). With a photographic interpretation function now co-located at the RFC squadron, the form of the distribution changed. When a photograph reconnaissance aircraft landed, proof copies were printed as soon as the photographic plates were developed. These copies would be annotated, by the BIO or his staff, showing any changes in the German defences disclosed by comparison with previous HOC photographs and then distributed as a priority, within 30 minutes, to the GS Intelligence officers at Army HQ, Corps HQ and Heavy Artillery, and Division HQ and Artillery.

Figure 16. Corps Squadron – Aerial Photograph Tasking and Distribution from 1917.

A second issue that expanded the distribution down to Company level when required followed approximately six hours later. (Hahn, The Intelligence Service within the Canadian Corps 1914-1918. pp. 118-119.). Figure 17 illustrates a BIS annotated proof vertical photograph.

Figure 17. Vertical annotated proof print. (Source: Mapping the Front; The Western Front Association Ypres – British Mapping 1914 – 1918 DVD )

All down the distribution chain, the photographs would on arrival be re-examined and used from the perspective of the receiving unit. From 1917 on, a soldier at platoon level could expect to carry out trench raid mission rehearsals behind the British line in an exact replica, derived from aerial photography, of the German trench system he was going to raid. Although preparations did not always go smoothly:

‘Thursday 15 February 1917 - Considerable panic over photographs. Everyone who is going to have a raid naturally wants photographs of the trenches they propose to enter, but as a rule they let us know about a day before the raid when it is probably quite cloudy. (Hughes, ‘Diary’of T McK Hughes IWM).

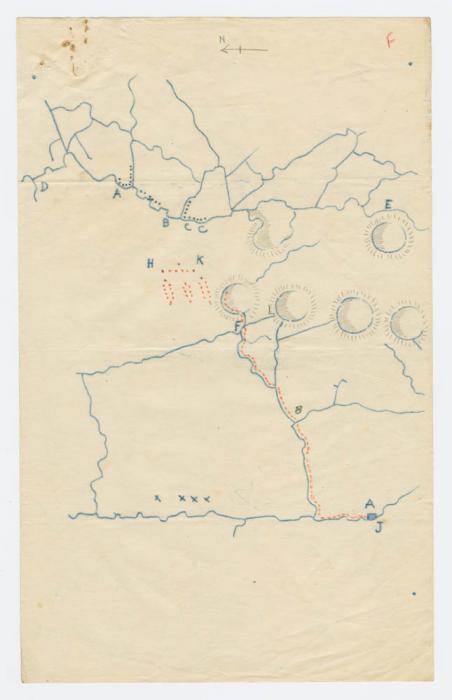

The photographs would also have been used by the officer commanding the raid to generate a sketch map that could be used by the other members of the raiding party. Figure 18 illustrates an aerial photograph derived sketch map used in the Roclincourt area by members of the 2/14th Battalion London Regiment who conducted a trench raid on 19 September 1916.

Figure 18. Aerial photograph derived sketch map. "The Body Snatchers": Trench Raid at Roclincourt https://digitalcollections.mcmaster.ca/pw20c/case-study/body-snatchers-trench-raid-roclincourt

Battle rehearsal also benefited; prior to their assault on Vimy Ridge in 1917 the Canadians built a scale model of their assault area based on aerial photographs (Figure 19). Whole divisions were taken to view the model as part of their battle training and preparation.

‘In an area well behind the lines, a large model of the Ridge, showing every phase of the German defence positions as gleaned from aerial photographs was laid out. In turns our battalions were taken back to this model, where, on a simulated pattern, they were shown exactly what they had to do and where they had to go on the day of the assault.’ (Bloody April p 119-120)

Figure 19. Vimy Ridge trench model 1917. (Source: Wikipedia)

Amiens in 1918 saw a proliferation in aerial photographs being made available at company level for study before the attack. In addition the following products and photographs were issued to the attacking troops:

(a) A Mosaic of each Divisional front, squared and contoured and freely annotated, for distribution down to N.C.O’s.

(b) Oblique Photographs of each Divisional front, for distribution to all officers. Australian Corps Battle Instructions for 8th August 1918, quoted in: Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 447.

Ultimately situational awareness was facilitated at every level through the availability and local exploitation of aerial photography.

Actionable Intelligence

The trench map and the processes used to maintain the map’s intelligence currency provided a framework onto which could be fused intelligence from other sources. This section will explore the evolution of counter-battery artillery intelligence fusion, a classic example of the operational/intelligence interface where aerial photography fulfilled a crucial role in providing and/or corroborating intelligence that could then be acted upon.

The Artillery Counter Battery Role

Not until the end of 1915 was the counter-battery role recognised as a separate tactical operation of the artillery requiring special organisation and co-ordinated intelligence support. At this stage the compilation of the first large scale 1:10,000 maps had made it possible to accurately plot many of the German artillery battery positions visible on the ever increasing numbers of aerial photographs. This process highlighted the discrepancies in and between the various counter-battery lists of the period that were being derived from RFC visual reconnaissance reports, RA observation reports, Corps INTSUMS and the fledgling reporting from the flash spotting sections. A report written in September 1915 had already highlighted the key failing in the contemporary counter-battery intelligence gathering processes:

‘. . . the important and rather difficult point then arises of the proper collation of all results, . . . (Winterbotham, Survey on the Western Front. p. 42.)

The First Compilation Section

In an attempt to address the collation issue Third Army set up a Compilation section under the control of its Topographical section in December 1915. This Compilation section was headed by the previously mentioned Lieutenant Goldsmith. As well as the study of air photographs, Goldsmith’s stated role was to synthesise and record the counter-battery intelligence from all sources and to disseminate, in INTSUM form, lists of German artillery positions derived from Third Army’s observation and flash spotting sections that he had correlated with the other intelligence sources. Goldsmith had identified the utility of using aerial photography coupled with the map to corroborate the other available artillery intelligence sources. With the establishment of FSC’s in February 1916 each army had its own Compilation section.

From early 1916 counter-battery intelligence was rationalised and coordinated at army level. In each army a weekly list of ‘Active Hostile Batteries’ that consolidated the information from the RFC and the FSC’s was issued every Sunday, coincident with a weekly counter-battery conference where the following were present or represented: General Officer Commanding (GOC) Heavy Artillery, GOC RFC Brigade, GSO Intelligence of the army and the OC of the FSC (Winterbotham, Survey on the Western Front. p. 43.). These conferences that continued until September 1916 would ascribe a confidence level to the batteries listed, those identified on or confirmed by aerial photography would be categorised as ‘position determined’. From May 1916 with the weekly lists growing longer and taking more time to plot, the details were also transposed onto a counter-battery target map and represented graphically.

Lessons from the Somme

The increase in operational tempo during the Somme and changes to the German artillery tactics exposed the weaknesses in centralising counter-battery intelligence at army level:

‘During this battle [the Somme] German Artillery tactics changed considerably. Protection gave way to concealment, and positions changed with a rapidity which made an Army compilation out of date almost as soon as lists or maps could be produced.’. (Winterbotham, Survey on the Western Front. p. 45.)

GHQ in early 1916 had already recognised the importance of counter-battery intelligence and had imposed an Intelligence Corps officer on the RA at corps level. Francis Law the Irish Guards infantry officer mentioned previously was one of those officers. Law had no artillery or intelligence experience:

‘Despite my ignorance of artillery I was given . . . a completely free hand. Every morning reports reached me from a variety of sources. . . . infantry battalions, brigades and divisions . . . artillery units . . . sound ranging sections [formally established in April 1916] . . . the [RFC] and . . . kite balloon sections. All gave bearings from their own positions to points behind enemy lines from which gun flashes had been spotted . . . I set up three large-scale maps, and plotted and recorded relevant information daily. When several sources had reported enemy activity at a common point I alerted all sources. I could and did ask the [RFC] to carry out reconnaissances and to photograph suspect areas. . . . I only called for [aircraft] sorties when verification of a target was thought to be vital. (Law, A Man at Arms. pp. 73-74.)

Law had found like many of his contemporaries that aerial photography was both a unique intelligence source and a corroborative tool that could be used to validate his other intelligence sources. With a Sergeant and a small clerical staff he conducted the artillery intelligence fusion role, what is now know as Surveillance and Target Acquisition (STA). Having determined the targets, what was needed was an evolutionary shift in command and control that would formally link the STA element to the contemporary counter-battery effort.

Establishment of the Counter Battery Office at Corps Level

This shift came during the winter of 1916/1917 when as a result of the lessons from the Somme a Counter Battery Office (CBO) commanded by a Counter Battery Staff Officer (CBSO), a Lieutenant Colonel, was formally established by GHQ at each Corps. November 1916 had witnessed the appearance of the first unofficial CBSO in Three Corps. Each CBO contained intelligence and operations elements with responsibilities that included; collecting, compiling and disseminating counter-battery intelligence and providing detailed arrangements and issuing orders for counter-battery work (Albert P. Palazzo, ‘The British Army's Counter-Battery Staff Office and Control of the Enemy in World War I’, Journal of Military History, 63:1 (1999:Jan.) p.64.). Manning levels were modest totalling approximately 12 personnel. As well as the CBSO there was a Staff Captain, an Intelligence officer and one or two Lieutenants. The other ranks comprised; two NCO’s, four clerks, three telephone operators and a draughtsman (Palazzo, ‘The British Army's Counter-Battery Staff Office and Control of the Enemy in World War I’. p.64, and Uniacke Papers, Remarks on "Notes on the work of a Counter Battery Office," c. late 1917 (XV Corps), Royal Artillery Institute, U/VIII/9, contained within: Saunders Marble, “The Infantry cannot do with a gun less”: The Place of Artillery in the BEF, 1914-1918, (Columbia University Press – Gutenberg-e)). The Intelligence officer was one of the new War Office sanctioned Royal Artillery Reconnaissance Officers (RARO) also newly established, at Army, Corps, and Corps Heavy Artillery Headquarters, during the winter of 1916/1917. The role of the RARO was clearly stated:

‘. . . to carry out special artillery reconnaissance, to study and collate the information derived from aeroplane photographs and maps so far as it affects the artillery, and to keep in close touch with the Royal Flying Corps. (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 233.)

There was a clear separation in the responsibilities of the Compilation section run by the FSC’s at army level and the compilation conducted by the CBO at corps when it came to aerial photograph interpretation. The CBO had primacy on determining the ‘fact of’ and activity status of any German artillery identified. The FSC were responsible for determining the precise location of any identified artillery (Winterbotham, Survey on the Western Front. p. 46.).

For the first time there was an intelligence/operations interface which enabled the results of the intelligence fusion to be acted on immediately. The success of the CBO initiative was clearly evident at Vimy Ridge in 1917. Lieutenant Colonel A. G. L. McNaughton the Canadian Corps’ first CBSO attributed the success to the fact that:

‘Each CBO kept detailed scheme diagrams for all systems. They ensured that Canadian guns were on a common survey scheme to Canadian locating assets. They had guns for counter-battery tasked to them for extensive periods of time, and kept extremely accurate logs and diaries that permitted the effective engagement of targets by minimising the knowledge gap of the enemy. In other words, by being highly organised and influential, the CBO was able to take the lead in the fight, which led to such impressive results.’. A.G.L. McNaughton referenced in: Richard Little, A Short History of Surveillance and Target Acquisition Artillery, Canadian Army Journal, Vol. 11.3 Fall 2008.

The Canadian CBO had correctly identified 173 of the estimated 212 guns that the Germans had available to defend Vimy Ridge, an impressive 83 percent success rate (Bill Rawling, Surviving Trench Warfare, (University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1992) p. 111.). Much of the identification success was attributed to aerial photography (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 236.).

Part 1 - The Pre-Cursor 1849 to August 1914Part 2 - The Beginnings August 1914 to January 1916

Part 3 - Aerial Photography comes of age

Part 4 - The Uses for Aerial Photography

Knowledge Version 2 1.1