Knowledge Centre- Subject Index Main Help page |

Aerial Photography

by Tim Slater

Part 1 - The Pre-Cursor 1849 to August 1914

Part 2 - The Beginnings August 1914 to January

1916

Part 3 - Aerial Photography comes of age

Part 4 - The Uses for Aerial Photography

Part 3 - Aerial Photography comes of age

Kitchener’s Volunteers – a new RFC Structure

The arrival late 1915 and early 1916 of Kitchener’s volunteers changed the BEF into a mass army forcing another change on the growing RFC. A new command structure was required to cater for a planned 60 service and 20 reserve Squadrons. This was outlined in two Army Council letters dated 25 August and 10 December 1915:

‘The RFC in the Field, currently divided into three wings, each attached to an army headquarters, was to be reconstituted as a brigade. As fresh units became available, new brigades were to be formed until there was one for each of the BEF’s armies. It was originally planned that each brigade would comprise three wings, but in the event there were only two until the middle of 1918. One, designated the Corps Wing, was for general [Corps level] co-operation duties; the other, designated the Army Wing, was for army reconnaissance, bombing and air fighting duties.’. Malcolm Cooper, The Birth of Independent Air Power (London: Allen & Unwin, 1986), p. 33.

The new Brigade formation came into effect on 30 January 1916 and by the start of the Somme there were four RFC brigades, one for each army, and a Headquarters Wing attached directly to GHQ. Under the new organisation each Corps now had an attached RFC squadron under its control and the Corps staffs were responsible for photographic reconnaissance tasking along the Corps front up to a depth of 5,000 yards. Beyond this aerial photography was the responsibility of the Army Wing.

Decentralisation of Photograph Reproduction

By the spring of 1916 the demand for photographs was overstretching the capabilities of the Wing photographic sections causing unacceptable delays in print delivery to demanding units. The solution enacted in April 1916 was to decentralise and establish a small photographic section, comprising a non-commissioned officer (NCO) and three men, at each of the Corps squadrons and in each Army reconnaissance squadron. Additionally each RFC Brigade was established with two RFC Photographic Officers, one notionally located at the Corps Wing the other at the Army Wing.

The training for the new photographic sections was carried out at Farnborough and included; the use and maintenance of aerial cameras, developing and printing plates, print titling and enlargement, the production of photograph mosaics, map reading and plotting. The role of these new sections was therefore camera maintenance, photographic processing and print production. As Laws describes:

‘ [On landing] . . . the plates where rushed into a darkroom on the squadron, processed and printed. . . . the first prints went to the local army headquarters, brigades, and sometimes down to company commanders. Then the negative would go back to the wing. They would make a distribution to the higher armed formations.’. Frederick Laws, quoted in: Joshua Levine, On a Wing and a Prayer, (London, Collins, 2008), p. 136.

Continued Uneven Development of Photographic Interpretation Skills

The interpretation of the photographs was being done elsewhere in intelligence sections by the recipients of the prints, many of whom had limited or no photographic interpretation experience. The Army Topographical sections had expanded and were subsumed within newly created Field Survey Companies (FSC) in February 1916. Each Army had its own Field Survey Company that was responsible for; fixing the position of British artillery batteries, Map drawing and distribution, Observation and flash spotting, sound ranging, and counter battery intelligence compilation. Within the organisation of a FSC was a Compilation section that had the role of synthesising the artillery counter-battery intelligence at army level. By this stage of the war each Army had a Staff Officer designated to study air photographs, within Third Army the officer was a Lieutenant Goldsmith. Goldsmith described as ‘one of the pioneers in the scientific study of air photographs’ was a compiling officer in Third Army’s Compilation Section (H. H. Hemming, Private Papers of H H Hemming, IWM Catalogue Number 12230 PP/MCR/155.). One of his stated duties was:

‘To study the interpretation of air photographs, and to that end the system and type of enemy works.’. H. Winterbotham, Survey on the Western Front (Provisional Report), (Maps, GHQ, 20 Dec 1918) p. 42.

By comparison in August 1916 Francis Law, an Irish Guards infantry officer being given a rest from the front, reported to Headquarters IXth Corps. His role for two months was as the Corps artillery intelligence officer where one of his jobs was the interpretation of aerial photographs. He was one of many officers with no photographic interpretation or intelligence experience assigned temporarily by Charteris to intelligence duties during 1916 (Francis Law, A Man at Arms (Collins, London, 1983) pp. 73-75.). Both the BEF and its intelligence requirements had expanded exponentially leaving Charteris with little choice.

Aerial photography over the Somme

Aerial photography over the Somme area had begun well before July. By the end of May 1916 the German first, second and third line defensive system had been photographed to a depth of more than 20 miles, and during the preliminary bombardment the first and second German lines were photographed again to determine how effective the British bombardment was. Throughout the Somme aerial photography was continuously asked for. The GSO 2 Intelligence of the First ANZAC Corps stated in his diary that he:

‘. . . was kept very busy [along with his other intelligence officers] interrogating prisoners, studying air photo’s, map making, issuing daily Intelligence Reports and so on.’. S. S. Butler, Private Papers of S S Butler, IWM Catalogue Number 9793 PP/MCR/107.

Photographic Intelligence Reporting

The increase in availability of aerial photography can be clearly discerned in the First ANZAC Corps intelligence summaries (INTSUMS) written during 1916.

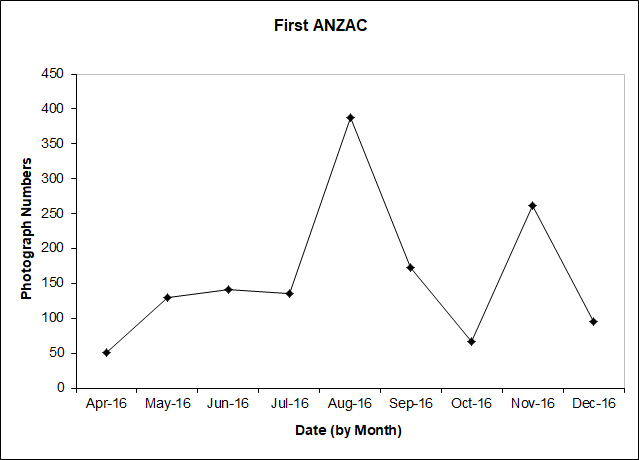

Figure 10. Numbers of aerial photographs available to First ANZAC Corps 1916. (source: AWM4-1-30)

Figure 10 provides a monthly summary of the number of aerial photographs listed as available to the Corps in the Corps daily INTSUMS. The obvious peak in photograph numbers, August 1916, correlates to the battle of Pozières (23 Jul - 3 Sep 1916) in which First ANZAC Corps were heavily engaged whilst the second peak in November correlates with the First ANZAC Corps attacks at the close of the Somme battle in the area near Gueudecourt and Flers. In addition to the quantitative increase in the availability of aerial photography during the Somme campaign, what could also be discerned from the INTSUMS was a qualitative increase in the extraction of the photographic intelligence.

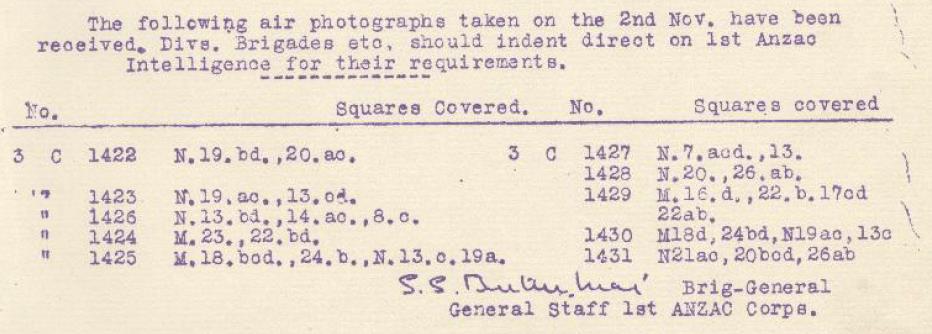

Figure 11. Photograph ‘Shopping List’. (source: AWM4-1-30)

During April and May 1916 the INTSUMS provided little more than ‘shopping lists’ of available photographs that could be ordered by subordinate units from First ANZAC Corps intelligence (Figure 11). From June onwards every two or three days the INTUMS started to contain textual summaries outlining the activity observed on the photographs taken in the intervening period. Between June and early November the fidelity of the reporting also changed, simple trench construction updates changed to include summaries of track usage, resupply choke points worthy of artillery attention, and the location of possible German headquarters elements.

Figure 12. Textual summaries outlining the activity observed on the photographs. (source: AWM4-1-30)

From late November the textual summaries were provided alongside the list of photographs they related to, usually in the INTSUM the day after the photograph was taken (Figure 12).

By the close of the Somme intelligence updates based on aerial photography were provided down to Brigade level in First ANZAC Corps. At the top of each INTSUM it stated ‘NOT TO BE TAKEN FURTHER FORWARD THAN BRIGADE HEADQUARTERS’. Further downward dissemination relied on the developing intelligence structures at Brigade and Battalion level. In comparison the daily INTSUMS issued by Second ANZAC Corps during the Somme period contained ‘shopping lists’ of available photographs and at the end of each month a textual summary of the German trench construction noted on aerial photography during the preceding month. Second ANZAC had arrived in France during July 1916 and held a quiet section of the line near Armentières north of the Somme area by the Belgian border. The lack of detail in their intelligence reporting is more likely a reflection of the operational tempo being experience by the Corps rather than an indictment on the skills of the Corps photographic interpretation specialist.

TCPED Incoherence and Duplication

From July to November 1916 the RFC took over 19,000 aerial photographs from which approximately 430,000 prints were made (Eaton, APIS Soldiers with Stereo, p. 6). In general terms this equated to approximately 22 copies of each photograph being produced and distributed.). The ever increasing volume of aerial photography exposed incoherence and duplication in the BEF’s aerial photography Tasking Collection Processing Exploitation and Dissemination (TCPED) processes.

Intelligence Specialists at Squadron Level

Early in 1916 the RFC had realised that it was not making full use of the intelligence collected or assimilated by its aircrew. From mid 1916 Recording Officers (RO’s), of Captain/Lieutenant rank, began to be appointed in RFC squadrons. The RO’s acted as intelligence officers and the squadron Adjutant and were tasked with debriefing aircrew collating the information gathered and forwarding anything of value to headquarters. In addition the RO’s in the Corps squadrons took on the artillery and infantry liaison role to reduce the burden on the Squadron Commanders (Hughes, ‘Diary’ of T McK Hughes.). The appointment of RO’s was recognition of the need for an intelligence function at squadron level. Despite this initiative the sheer volume of information generated during 1916 coupled with a parochial view taken by many squadron RO’s, largely caused by a lack of formal intelligence training, meant that a wealth of intelligence information was just carefully filed. The RFC had wanted to call its RO’s ‘Intelligence Officers’ but GHQ Intelligence had refused to sanction the name or the role and was adamant that such a role would fall under the purview of the intelligence staffs.

A British study of the French intelligence system published in September 1916 highlighted the advantages of integrating an intelligence specialist at squadron level (The National Archives, WO 158/983, Notes on the French system of intelligence during the battle of the Somme (September 1916).). With this study in mind in October 1916 Trenchard, now the Major General in command of the RFC in France, proposed that intelligence sections be established at squadrons and wings with reconnaissance and photographic responsibilities ‘where the Intelligence Officer could be in intimate touch with the flying and photographic personnel’ (H. A. Jones, TheWar in the Air Volume 3 (Oxford, Clarenden Press, 1931) p.315.). From late October an experimental intelligence section commanded by Captain G. T. Tait, an attached Intelligence Corps officer, was established at 3 Squadron RFC, the squadron subordinated to First ANZAC Corps during the latter stages of the Somme (Australian War Memorial, Honors and Awards - Gerald Trevredyn Tait, (25 Dec 1917)). The experiment was deemed a success, and during December 1916 instructions were issued to form Branch Intelligence Sections (BIS’s) at the headquarters of each corps squadron and each army wing. The BIS’s, commanded by an Intelligence Corps Officer called a Branch Intelligence Officer (BIO), comprised; two draughtsmen, one clerk and an orderly. The sections role was clearly defined:

‘To interrogate every observer and ensure that full advantage be taken

of such information as he might possess.

To disseminate to all concerned with the least possible delay information

obtained by the Royal Flying Corps which required immediate action.

To examine and, where necessary, to mark all photographs and to issue both

photographs and sketch maps illustrating the photographs.’. Jones,

The War in the Air Volume 3. p.315.

The Official History states that: ‘Although the sections formed part of the Army or Corps Intelligence they were placed under the direct orders of the officer commanding the wing or squadron . . .’. Jones, The War in theAir Volume 3. p.316.

The reality may have been different. Lieutenant Thomas Hughes, the BIO attached to 53 Squadron in 1917, shows clear animosity towards his Squadron Commander in his diary. His refusal to comply with his Squadron Commander’s order relating to situation maps and his deference to Corps Intelligence guidance would suggest that the BIS’s came under the purview of GS Intelligence (Hughes, ‘Diary’ of T McK Hughes.). During 1917 there was a trend in some Corps to publish a daily situation map as part of their daily INTSUM. The situation maps were an RFC driven initiative and in the participating corps were produced by the BIS. Hughes an experienced photographic interpreter was sceptical about the value of these maps, his scepticism centred on accuracy and production time. Produced at 1:20,000 scale and annotated with activity derived from aerial observation and photography they presented a quick visual update unsuitable for determining accurate positional data. In Hughes’ opinion the intelligence content also suffered. A review of the II ANZAC Corps INTSUMS during 1917 supports this view, INTSUMS issued with a situation map contained limited aerial photograph derived textual updates.

Corps Topographical Sections

Much to the chagrin of the RE’s, with the exception of the Intelligence Corps Officer, the manpower for the BIS’s came from the newly forming Corps Topographical Sections. Raised as an integral part of the FSC’s they were subsequently detached to Corps Headquarters where they worked under the immediate direction of the GS Intelligence. During the Somme the need for rapid dissemination of information about the constantly changing tactical situation had led to the devolution of certain aspects of map production from Army to ad-hoc topographical sections at corps level (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 224.). Although not officially authorised until January 1917 the first Corps Topographical Sections appeared in Fourth Army in December 1916. The RE’s had their own view on the role of the BIS’s:

‘Branch Intelligence Sections had been formed about the same epoch [as Corps Topographical Sections], and for some time there was considerable overlapping of work, and doubt as to their exact relative spheres. The Branch Intelligence Section was instituted for the information of the Royal Flying Corps Pilots themselves, rather than for the reproduction and sketches for Corps and Divisional Troops. The latter duty falls to the Topo Section.’. Winterbotham, Survey on the Western Front. p. 50.

In direct contradiction to the RE’s perception the Canadian Corps viewed the utility of the BIS’s differently:

‘One of the most important functions [of the BIS] is the examination of aeroplane photographs, interpreting them with respect to topography in the enemy’s country, as well as annotating works and defences prior to their issue.’ Hahn, The Intelligence Service within the Canadian Corps 1914-1918. p. 260.

The ‘Branch Intelligence Officer is a Canadian Corps Officer who lives with the Squadron of the R.A.F. covering the Corps front, and with whom the Intelligence Branch communicates if they wish any particular mission carried out by the R.A.F. This officer is further an expert in Aeroplane Photographs, and transmits any information he may glean at the Squadron Headquarters to Intelligence Branch at Corps Headquarters.’ REPORT of the MINISTRY, Overseas Military Forces of Canada 1918. p. 217

Synergy between BIS and Corps Topographical Section

In reality the functions of the BIS’s and Corps Topographical Sections complemented each other. The BIO at the BIS was the conduit through which all the Corps aerial reconnaissance and photography tasking flowed. His unique position gave him oversight of the Corps operation intelligence requirements thus enabling him to quickly prioritise intelligence gleaned from aircrew debriefs, reconnaissance reports and his section’s photographic interpretation efforts. Time critical intelligence was disseminated immediately by telephone and when necessary followed up with annotated photographs and/or photograph derived sketches. A textual summary of activity derived from any photographic interpretation would subsequently be included in the Corps INTSUM, at the latest the day after the photograph was taken. Corps Topographical Sections, although not empowered to produce formal background maps, this role remained at Army level, were responsible for the production of ‘hasty’ maps and sketches at short notice to support on-going Corps operations. The nature of the work, which included producing trench map overlays showing the latest changes and Barrage and Counter Battery overlay maps, resulted in these sections taking a more considered view of the aerial photographs taken. The results of their photographic interpretation were incorporated on the maps and sketches they produced. In addition textual summaries of activity derived from any photographic interpretation that complemented the BIS reporting would be included in the Corps INTSUM up to two to three days after the photographs were taken. Immediate ‘first phase’ reporting was being carried out by the BIS’s, whereas considered ‘second phase’ reporting was being conducted by the Corps Topographical Sections. The birth of these two sections streamlined aerial photography’s TCPED process making it both coherent and efficient, thus enabling it to support both superior and subordinate units. The positive impact of these two sections serves to support and reinforce the view presented by Andy Simpson that:

‘From being a post box in 1914, the corps was becoming a vital clearing house for information by late 1916. Andy Simpson, Directing Operations (Brinscombe, Spellmount, 2006) p. 53.

Expansion of Photographic Interpretation Expertise

With the increase in demand for, and the wider distribution of, aerial photography came a corresponding need for more specialist intelligence staff in subordinate units to carry out the photographic interpretation. From late 1916 Intelligence Corps officers, trained to interpret aerial photographs, began to be attached to Divisional Intelligence sections (F M Cutlack, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918, Volume VIII – The Australian Flying Corps in the Western and Eastern Theatres of War, 1914–1918 (11th edition, 1941), pp. 206 - 207.). These officers were supported by an office staff of an aeroplane photo man, three draughtsmen and two clerks (Hahn, The Intelligence Service within the Canadian Corps 1914-1918. pp.113 & 119.). By the end of 1916 photographic interpretation skills had permeated down to divisional level. Structured training was required to push the skills down further.

Photographic Interpretation Guides

The first photographic interpretation practitioners, who included Romer (First Army’s Maps and Printing Section early 1915), Lloyd (First Corps Intelligence Officer 1915) and Goldsmith (Third Army’s Compilation Section 1916), all learnt their skills ‘on the job’. Photographic interpretation was so new that no training formal or informal was available. Slowly a body of experience was built up and was translated into guides and training courses. The first guides developed in an ad-hoc fashion and were genuine attempts by the early pioneers to share their new found knowledge. As already mentioned, Lloyd probably produced the first British photographic interpretation manual that was published in November 1916. Although early in July 1916 Moore-Brabazon, dissatisfied with the use being made of the RFC photography by the BEF’s intelligence elements, produced and circulated six copies of a photographic interpretation guide called Photographs taken by the Royal Flying Corps: (Moore-Brabazon, The Brabazon Story, (London, William Heinemann Ltd, 1956), p.96. Medmenham Collection DFG 1471, J.T.C. Moore-Brabazon, Letter to Squadron Leader Mayle, School of Photography RAF, 25 November 1959.). The covering note to the guide stated:

‘These photographs taken by the R.F.C. are put together in book form,

in the hope that they may be of use in furthering the closer study of aerial

photographs as an aid to reconnaissance.

I am indebted to the 3rd Brigade for most of the Photographs, and to Lieut

St B Goldsmith of the 3rd Field Survey Company in including his observations

of points of interest in them. J.T.C. Moore-Brabazon, Major R.F.C., R.F.C.

G.H.Q., 8/9/16’. (Copy owned by Mr Barry Jobling)

In early 1917 Rory Macleod, who had been the liaison officer between Fourth Brigade RFC and Fourth Army’s Counter Battery Intelligence Staff in 1916, produced a book on the interpretation of aerial photographs for Fourth Army’s Artillery School. (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 195.). By March 1917 the Intelligence Staff at GHQ had taken ownership of the photographic interpretation manuals and had issued S.S. 550 Notes on the Interpretation of Aeroplane Photographs which was distributed down to Battalion, Machine Gun Company and Trench Mortar Battery level (Finnegan, Shooting the Front. p.150.). This manual was updated in February 1918 S.S. 631 Notes on the Interpretation of Aeroplane Photographs (The National Archives, Notes on the Interpretation of Aeroplane Photographs, AIR 10/320.).

Photographic Interpretation Training

Photographic interpretation training developed in parallel with the interpretation guides. From early 1915, the RE’s were being trained to use aerial photography to support cartography. Also during 1915, Lloyd probably provided the first photographic intelligence related training classes, although they were arguably more capability awareness lectures rather than specialist practitioner training. Not until late 1916 was photographic interpretation incorporated into the syllabus of the 10 week Intelligence Corps Officer training course run in London near Wellington Barracks (Anthony Clayton, Forearmed – A History of the Intelligence Corps, (London, Brassey’s, 1993). p. 54.). By 1918 the photographic interpretation element of the Intelligence Corps Officer training course had matured significantly and focused on the uses of aeroplane photographs within intelligence sections at Division, Corps, and Army level. Exercises on the course required students, using aerial photographs, to make maps to plot onto and record information on machine-gun emplacements, artillery batteries, trench-mortars, and airfields, in a way that replicated what the BIO’s were doing in the field (Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing Vol. 74, No. 1, January 2008, pp. 81-82). For most of 1916 therefore photographic interpretation skills continued to be learnt on the job. As Francis Law (IXth Corps artillery intelligence officer) stated:

‘At first I found interpretation of aeial photographs difficult but did better with practice.’. Law, A Man at Arms. p. 74.

From late 1916 the newly appointed Intelligence Corps officers at both Division and the BIS’s had either been trained at the Intelligence Corps training school in London or in the case of reassigned officers, had attended the newly established eight day course on aerial photography run at Army level in France. Whenever possible post training familiarisation visits were provided to intelligence officers prior to them taking up their posts:

‘Saturday 24 February 1917 - Captains Bruce G.S.O. 3 of the 36th Division and one Barker who is Intelligence Officer to No 46 Squadron have been sent to spend the day with me as the culminating treat after an 8 day course of aerial photography.’. Hughes, ‘Diary’ of T McK Hughes.

Evolution of Photographic Interpretation Awareness Training

Following the formal establishment of the photographic interpretation practitioner training in late 1916, 1917 witnessed the formalisation of awareness training. By June 1917 the following courses, all of which contained aerial photography in their syllabus, were advertised in S.S. 152 Instructions for the training of the British Armies in France (Provisional) (S.S. 152, Instructions for the training of the British Armies in France (Provisional), (HMSO June 1917).):

* The Army Infantry School, training Company Commanders, Company Sergeant

Majors and Sergeants.

* The Army Scouting, Observation and Sniping School training officers intended

to become Brigade or Battalion Intelligence Officers.

* The Army Artillery School training Artillery Officers.

* Corps Infantry School training Platoon Commanders and Platoon Sergeants.

The success of the awareness training is evident in an anecdote provided by a British company commander. In 1917 C. J. Lambert with his Company of Royal Scots were occupying a sector of trenches near the Sencee River. Their lives were being made miserable by a German Mortar which defied all attempts to pinpoint its location using the routine aerial photographs available as it was too well hidden. In a further attempt to locate the mortar Lambert requested a dawn photograph in the hope that any tracks made by the mortar crew in the grass moistened by the early morning dew would reveal the mortar’s precise location. In his own words Lambert describes the result:

‘In due course I was handed a composite photograph which told me everything I wanted to know. It was a poor day for the trench mortar crew, . . . for the mortar ceased to trouble us following a call to our supporting artillery.’. Medmenham Collection DFG 3410, Letter Lambert to Babingdon-Smith, 23 Dec 1957.

A key success that justified the organisational changes and the efforts being put into photographic interpretation training came during Third Ypres. Haig in his diary entry for the 28 August 1917 recorded:

‘Trenchard reported on the work of the Flying Corps. Our photographs now show distinctly the ‘shell holes’ which the Enemy has formed turned into a position. The paths made by men walking in rear of those occupied, first caught our attention. After a most careful examination of the photo, it would seem that system of defence was exactly on the lines directed in General Sixt von Armin’s pamphlet on ‘The Construction of Defensive Positions’ . . .’. Gary Sheffield and John Bourne eds, Douglas Haig War Diaries and Letters1914-1918, (London, Phoenix, 2006) p. 320.

The II ANZAC Corps INTSUMS had begun to highlight the use of shell holes in late July:

‘. . . tracks lead to the river bank just north of the village, C 11 a 55.50 opposite the farms on the western bank; these run to shell holes or places where machine guns could be fired from (42B 1693).’ Australian War Memorial, II ANZAC INTELLIGENCE SUMMARY to 6 p.m. 23rd July 1917, AWM4/1/33/15 Part 2.

Following this discovery of what was the German defence-in-depth system the weight of British artillery barrages was switched onto the shell holes. This change increased German casualties and dislocated their defensive system.

By the end of 1917 personnel with a remit to carry out photographic interpretation were located on the Intelligence Staff at Infantry Brigade and Battalion level. The Brigade and Battalion Intelligence officers would have attended the ‘The Army Scouting, Observation and Sniping School’ whilst the support staff were trained at Division or Corps level by an aerial photograph expert. During early 1918 Hughes (BIO 53 Squadron) conducted a number of these training sessions:

‘Thursday 17 January 1918 - I went to Corps to give my famous lantern lecture to a new group of would be Intelligence Officers from the trenches. Hughes, ‘Diary’ of T McK Hughes.

The BEF of 1918 had succeeded in placing photographic interpretation personnel, trained to the appropriate standard, in intelligence sections at all levels.

Figure 13. Intelligence and Photographic Organisation c1917.

Part 1 - The Pre-Cursor 1849 to August 1914Part 2 - The Beginnings August 1914 to January 1916

Part 3 - Aerial Photography comes of age

Part 4 - The Uses for Aerial Photography

Knowledge Version 2 1.1